|

|

Vol.

34 No. 3

May-June 2012

by Guillaume Minnoye and Nataša Doslik

With the world population set to grow by 50 percent by 2050, innovative solutions will be needed to tackle global challenges such as access to drinkable water, food, health, and clean and safe energy. Research in chemistry-related fields—and its application in industry—holds great potential for finding answers to many of these problems. But the success of any innovative effort very much depends on having a solid system of patent protection.

Patents give inventors the exclusive right to prevent others from exploiting their invention for a limited time, in exchange for disclosing the details of the invention. This acts as a strong incentive to innovate. Indeed, many important inventions might not have seen the light of day without the patent system.

The patent system has come a long way since the first patent law was established in Europe in the 15th century. Recognizing the need for closer cooperation on patent protection, 16 countries signed the European Patent Convention in 1973, setting up an international organization, the European Patent Organisation with its executive body, the European Patent Office (EPO). Today, the organization has 38 member states and three associated states. Together they cover a territory with a population of almost 600 million people, which outnumbers that of the USA, Japan, and Korea combined. With nearly 7 000 staff, the office is one of the largest European institutions and has an entirely self-financed annual budget of EUR 1.8 billion. The EPO has its headquarters in Munich, and offices in The Hague, Berlin, Vienna, and Brussels.

The EPO provides a central one-stop service to innovators—whether individual inventors, universities, research institutes, or companies—from Europe and around the world. It enables them to obtain patent protection in up to 40 European countries concurrently by filing a single patent application in one of the EPO’s three official languages (English, French, or German). This makes it the largest transnational patent system in the world. Since no unitary EU-wide patent yet exists, patent applicants need to select the countries in which they would like protection. The patent granted by the EPO has the same legal effects as a national patent does in each of these countries.

Patents are granted by the EPO only for inventions that are new, involve an inventive step (i.e., are not obvious to a person “skilled in the art”) and are industrially applicable. While the patent system is generally open to all technologies, there are a number of exceptions to patentability under European patent law, such as scientific discoveries, mathematical formulae, aesthetic creations, and methods of doing business, to name a few. Other restrictions are found in the area of biotechnology. For example, European patents cannot be granted for human embryos, plant and animal varieties, or essentially biological processes for the production of plants and animals (e.g., breeding methods involving conventional steps such as crossing and selection).

The EPO’s growth reflects the success and economic importance of the European patent: the number of European patent applications filed in 2011—243 000—was more than eight times higher than the originally predicted maximum of 30 000, and the figures are still growing. The office has a worldwide user base, with most filings (about 60 percent) coming from outside Europe. The EPO has witnessed a considerable growth in filings by Chinese, Korean, and Japanese firms over the past two years. These companies often choose to file international applications at the EPO under the Patent Cooperation Treaty, an agreement that makes it possible to file for patent protection in more than 140 countries on the basis of a single application. The EPO acts as International Searching Authority in more than 40 percent of all Patent Cooperation Treaty procedures, making it a nerve center of the global patent system and a central pillar of not only European, but also global innovation.

The importance of chemistry for global research and industry is mirrored in chemistry-related patents at the EPO. Of the office’s 4 000 patent examiners, nearly 1 200 of them examine patents in chemistry-related fields, including inorganic chemistry, organic chemistry, polymer chemistry and biotechnology. The EPO receives patent applications for inventions covering a hugely diverse range of technical areas: from artificial skin and biomarkers for tumors to Alzheimer’s drugs; from cosmetics and detergents to paints; from solar and fuel cells and batteries to sensors; from baby and functional food to water treatment, just to name a few. The chemistry-related technical fields are not only very diverse, but are constantly undergoing developments, thereby leading to new, emerging technologies, as well as causing established technologies to lose importance. Take the example of chemical processes used in analogue photography: this is a technical field which is disappearing and making room for digital photography. This change in technology has resulted in a shift in patent applications filed in new technical fields, many of which are no longer chemistry-related. The EPO is thus at the cutting-edge of technological trends.

Meanwhile there are also some stalwart technologies, which have been important over long periods of time. One example is cement. This material has been known, produced, and used for 2 000 years, so it may come as a surprise that a large number of patent applications are still filed in this technical field. This has many reasons: cement’s applications include a vast range of different possibilities, and research for improved characteristics of cement for different usage is ongoing, as it is still among the most frequently used building materials worldwide. And even in such a seemingly “old” technical field, new features can emerge. It is now acknowledged that the cement industry is a vast producer of carbon dioxide, so new production processes are being sought. As a result, the EPO receives an increasing number of patent applications which focus on carbon dioxide reduction, or the recycling of waste material (e.g., combustion residues such as fly ash originating from coal gasification) using cement.

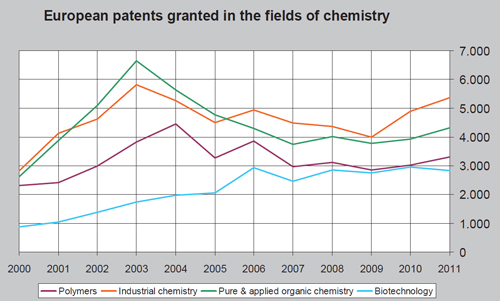

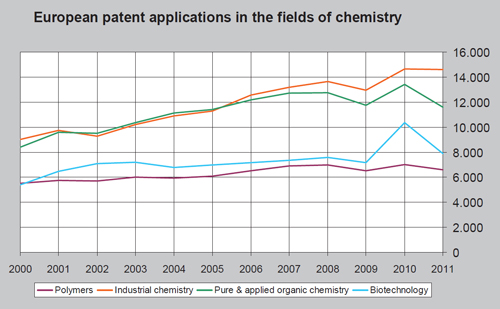

The EPO’s latest filing figures (see graphs) show a steady growth in patent applications in all areas of chemistry over the past 10 years, notwithstanding certain dips which can be attributed to the recent financial and economic downturns. Industrial chemistry and biotechnology, in particular, have seen very fast growth since 2000: with growth rates of 62 percent and 47 percent, respectively, for patent applications filed; and +223 percent and +90 percent for patents granted.

|

| |

|

A growing number of individual inventors and businesses are realizing the commercial impact of patenting their inventions. Patents give companies the possibility to reap the rewards of their investment and recoup development costs. They have also become an important tool for measuring a company’s R&D performance, as well as a trading and bargaining chip for cross-licensing and technology alliances. And many companies now consider it important to have a large patent portfolio to be recognized as a serious business partner and to raise capital.

Increasingly, patents are also moving on to the radar of academia. More and more public research institutions and universities are now patenting their inventions. Research institutions can start a company to commercialize their patent, or have it licensed by others, which in turn funds university research and opens up new possibilities for innovation.

The knowledge-transfer function of patents is not to be underestimated. In return for patent protection, the inventor has to disclose the details of the invention, which are published in the patent document. A large proportion of the world’s applied technical knowledge can therefore be found in patent documents. The availability of this information inspires further inventions and at the same time helps prevent the duplication of R&D work. The EPO’s public databases—containing more than 70 million documents and accessible on its website free-of-charge—are one of, if not the largest and most pertinent sources of information about state-of-the-art technology available anywhere in the world. In addition, in order to ensure maximum accessibility of these documents to inventors and researchers, the EPO has made the development of machine translation technology one of its top priorities.

Last year, the EPO broke new ground in removing the language barriers in the way of patent information by teaming up with Google to provide a free machine translation service to the public. The new service, called Patent Translate, can be expected eventually to cover the 28 languages of the EPO’s member states, plus Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Russian. It will be of huge benefit to companies, inventors, and scientists all across the globe, who will be able to easily access up-to-date information about the latest technologies, including those coming out of Asia, in their own language. A first set of seven languages (English, German, French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and Swedish) covering about 90 percent of all patents issued in Europe, has just been made available, a second batch covering another six languages is expected in 2013, and the rest will follow by the end of 2014.

The success of the European patent boils down, in essence, to three things: First of all, the EPO’s grant procedure, which rigorously aims for high patent quality, provides the highest legal certainty for innovation on the technology market. Before a European patent can be granted, every application at the EPO is subject to a thorough search and rigorous examination process by an examining division consisting of three highly qualified and trained patent examiners who have a university degree in the technology in question and are able to work in the three official languages of the EPO. This results in patents which are enforceable and stand up well to legal challenges. Only around 45 percent of all applications result in a patent, and almost all of the successful applications are modified or restricted during the examination process. In order to uphold its high level of quality, the EPO maintains the most comprehensive collection of patent and patent-related literature in the world, containing more than 600 million records in over 120 databases, updated daily, as well as over 70 million patent documents from all industrialized countries. The office has also developed expert tools for patent examiners to conduct a state-of-the-art search. The outstanding quality of European patents has been acknowledged time and time again by experts in independent surveys.

Secondly, owing to the efficiency and transparency of the European procedure, information on the patentability of an invention is publicly available at an early stage: the office releases a first estimate on patentability as early as six months after filing of the application with the EPO. Few other offices with an international remit are able to provide information so quickly and reliably.

Finally, the harmonizing nature of the European patent system proves useful in integrating new member states into the European innovation process and is conducive to a prompt dissemination of new technologies. That is why associate status is so attractive to neighboring non-European countries, as is shown by an agreement with Morocco, and why more and more aspiring regions, like ASEAN, see the European patent system as a suitable model for developing their own intellectual property systems.

Despite its resounding economic success, the current system of patent protection in Europe is still structurally incomplete: Today, a patent holder choosing to have EPO-wide protection ends up with a bundle of 38 national patents. A true supranational patent for Europe has been discussed for decades, and the decision last year of 25 EU member states to introduce a unitary patent amounted to a political breakthrough in this respect. The creation of a unitary patent and a centralized, specialized European patent court will be an important step towards further supporting innovation by simplifying procedures and dramatically cutting the costs for anyone seeking patent protection in Europe. The office is proud to have been designated by the EU as the body which will grant the unitary patent and centrally administer it on behalf of the participating EU member states.

|

| Oral Proceedings in examination and opposition, part of the examiners’ work profile, are one of the pilars to ensure legal certainty. |

The positive developments in Europe and reforms of the patent system in the USA, in turn, have given fresh impetus to the efforts to harmonize the patent systems of the largest economic regions. Such alignment is needed in view of the growing interdependence of technology markets and the ever-greater influence this has on businesses’ global IP strategies, leading them to file parallel patent applications for the same invention in multiple countries. Businesses need to find comparable conditions in all markets if their innovation strategies are to succeed.

The EPO is working closely with the other major patent offices, especially those of China, Japan, Korea, and the USA in order to reduce unnecessary duplication of work in the global patent system, while at the same time guaranteeing the quality of patents granted.

One important milestone in cooperation was the agreement between the EPO and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to develop a joint system for the classification of inventions. The new Cooperative Patent Classification is based essentially on the European approach, and is a promising start to creating a worldwide standard, especially now that Japan and China are also considering adopting it.

Patents are increasingly in the public spotlight, in the concerns of citizens, and on the agenda of policymakers in Europe and worldwide. What was once an arcane legal instrument is now a much-talked about right of unprecedented economic importance in our current innovation- and information-driven global society. The EPO is actively participating in the debate about how the patent system should be reshaped to better serve the needs of society and industry, create jobs and economic growth, and promote the development of new technologies that will help us to tackle global problems such as climate change, disease, food and water shortages, and environmental pollution.

In the field of climate change mitigation technologies, for example, the EPO conducted a joint project with the United Nations Environment Programme and International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, a Geneva-based NGO, to gain a better understanding of the role played by patents in the deployment and dissemination of these technologies in developing countries. The study’s final report, published in September 2010, included the findings from a comprehensive mapping of clean energy technologies, an in-depth analysis of the patent landscape for these technologies, and a survey of licensing activities in this field. The technologies covered a wide range of areas including renewable energy sources (e.g., geothermal, hydro, solar, and wind), efficient operation of power networks, biofuels, energy storage, and hydrogen technology. One groundbreaking result of the project has been the creation of a dedicated classification scheme for patent documents relating to clean-energy technologies, which is now online. Using a searchable database, this new scheme gives users access to up-to-the-minute, accurate, and user-friendly patent information.

The EPO will make every effort to play its part in the development of sustainable and efficient patent system which responds to the needs of the economy and society both in Europe and beyond. In this perspective, its true potential and capacities as facilitator for innovation are only just about to unfold.

Guillaume Minnoye is the vice president of Directorate-General Operations at the EPO, which is responsible for search and examination of European patent applications and conducting of opposition proceedings in relation to European patents. Nataša Doslik <[email protected]> holds a Ph.D. in inorganic chemistry and is senior examiner in Industrial Chemistry in Directorate-General Operations at the EPO.

www.epo.org

Page

last modified 30 April 2012.

Copyright © 2003-2012 International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry.

Questions regarding the website, please contact [email protected] |