|

|

Vol.

34 No. 1

January-February 2012

by Brigitte Van Tiggelen and Danielle Fauque

Under the theme “Chemistry—Our Life, Our Future,” the International Year of Chemistry 2011 emphasized that chemistry is a creative science essential to solving many global challenges. Just as important, IYC 2011 was also a celebration of the history of chemistry and its many contributions to the well-being of humankind. Fittingly, the year coincided with two symbolic anniversaries in the history of the science: the centennials of Marie Curie’s Nobel prize in chemistry and the founding of the International Association of Chemical Societies (IACS), which was succeeded by IUPAC a few years later.

At the end of the 19th century, chemists already had a long record of international gatherings. One such early meeting was the infamous Karlsruhe meeting (see Nov-Dec 2010 CI, pp. 10–14). Though chemists were indeed exchanging ideas and undertaking sometimes heated discussions through journals and correspondence, the need for an agreement on writing chemical formulas and using the same scale for atomic weights prompted the young August Kekulé to gather chemists from all over Europe in early September 1860. With the help of his friend Carl Weltzien, and the support of reputed chemists such as Adolphe Wurtz, Robert Bunsen, Carl Fresenius, Jean-Baptiste Dumas, Stanislao Cannizzaro, Lothar Meyer, and Dimitri Mendeleev, Kekulé launched a call for delegates of all countries to gather in Karlsruhe. At that time, he was 31 years old and had been recently appointed professor of chemistry at the University of Ghent in Belgium.

The outcome of the ensuing debates at Karlsruhe surpassed the goal of standardization since during the meeting, the Italian chemist Stanislao Cannizzaro convinced most participants to adopt the fruitful distinction between atoms and molecules that had been suggested by Amadeo Avogadro almost half a century before. This first professional congress of chemistry was followed by a few others occurring on an irregular base and often with international fairs in the following 20 years (1867 in Paris, 1872 in Moscow, 1873 in Vienna, 1876 in Philadelphia, 1878 in Paris, 1880 in Düsseldorf, and 1889 in Paris).

By the end of the 19th century, chemists were attending other kinds of international meetings, such as the Congress of Pure and Applied Chemistry initiated in 1894 by the Belgian Chemical Society, a tradition that has continued to this day under the guidance of IUPAC (see Jul-Aug 2011 CI, pp. 11–14). They also attended more general meetings like those organized on the occasion of a universal exhibition or a world fair. Chemists also participated in regular meetings at the regional and national level, often organized by the national chemical societies, as well as international meetings on specific topics inside the wide domain of chemistry. National chemical societies made it a point of honor to send one or more delegate(s) to those meetings, so as to keep their members informed about advances in the field.

|

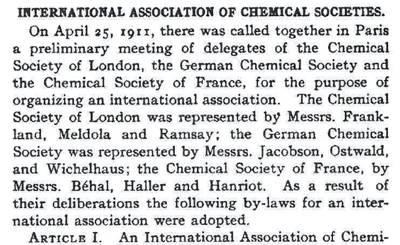

Report of the Foundation of the IACS in The Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry (August 1911, p. 614): Statutes and Decision of the American Chemical Society to join

(see full page here). |

It is on such an occasion, in September 1910, that a French chemist, Albin Haller, then president of the Société Chimique de France, took part in a meeting of the Société Suisse de Chimie (Switzerland) and came up with the idea of an international association of chemistry. The concept was met with enthusiasm by Wilhelm Ostwald with whom Haller discussed the idea. Before sending an open call to all chemical societies to join, Haller wanted to secure the official support of two of the most important countries in chemistry at that time: Germany and Great-Britain. He contacted the respective chemical societies with his plan for the formation of an International Committee that would consider questions of nomenclature and other matters in order to facilitate the comprehension of chemical literature. To IUPAC members this must sound familiar!

Following an enthusiastic response from London and Berlin, the French chemical society organized a first meeting on 25–26 April 1911 in Paris. At the meeting, attendees agreed upon the statutes for organizing the new association: each country would be represented by a society of pure chemistry or physical chemistry, and the number of delegates would be kept small. The goals, they decided, would be the unification of chemical nomenclature and the notations for chemical and physical constants. Following the official founding on 25 April, the attendees agreed to focus first on standardizing the nomenclature of inorganic chemistry, atomic weights (in collaboration with the International Committee of Atomic Weights), and symbols for physical constants. In addition, they discussed a system for gathering summaries of all chemistry papers, and ways to standardize publications to avoid the repetition of papers.

The next meeting of the International Association of Chemical Societies took place 13 April 1912 in Berlin under the presidency of Wilhelm Ostwald. Delegates from Russia, Italy, the Netherlands and the USA joined their peers from UK, France, and Germany agreed that the next course of action for the association would be the creation of international commissions that would study and decide upon matters of chemical nomenclature (organic and inorganic). It was also decided that the funding for this new international institution would be provided by the member societies.

Their was widespread agreement about the need for standardization, be it the size of publications, matters of notation, standard atomic weights, and chemical formulas, but when it came to making and enforcing these decisions, it was another matter. For example, delegates to the Berlin meeting agreed that the international format for journals should be 16 x 22,6 (cm x cm). But in November 1912, after much discussion, it was decided not to publish using this format, for reasons of cost.

|

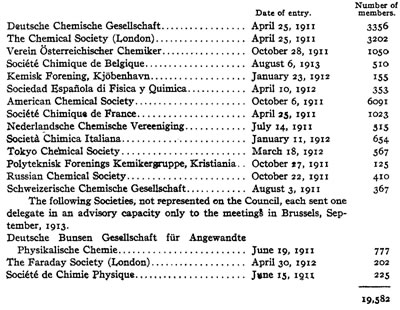

| List of Affiliated Societies in 1913, as published in Journal of the American Chemical Society (36, 1914), p. 83. |

Despite early optimism, delegates came to realize that the Promethean work (and its costs) of the new association could not be shouldered by the national societies alone. In early 1913, the lingering problem of funding seems to receive a solution. A conversation between Haller and the Belgium entrepreneur Ernest Solvay gave hope for the Future: the rich entrepreneur wanted to help fund the IACS, starting with 250 000 francs, to be followed by 55 000 francs every year for 29 years provided that the association held all its meetings in Brussels.

| . . . delegates came to realize that the Promethean work (and its costs) of the new association could not be shouldered by the national societies alone. |

Plans had already been made for the third congress to be held in London in September 1913, but Solvay was very clear that he wanted to host the IACS meeting and have it coincide with other anniversaries he intended to celebrate with splendor: 50 years since the founding of his company (Solvay et Cie) and a golden milestones in his own marriage. Haller was quite happy with Brussels, unlike Ostwald who would have preferred Berne or Geneva. However, the prospect of such generous funding was impossible to turn down. Thus, early in 1913, plans were made for the next meeting to take place in Brussels in 1913 and for an International Institute of Chemistry to be established there.

In spite of these early hopes, the IACS was short lived. The 1914 meeting never took place because of the war. And science that had been celebrated as an international venture whose benefits could be evenly shared by all nations suddenly became a national or patriotic pursuit. And the use of chemical weapons demonstrated the disturbing behavior of some chemists, behavior which manifested how scientists could be as impure as their science. Pure chemistry wasn’t that pure after all, since its achievements could lead one nation to victory and the other to submission.

What the first world war definitely demonstrated was the power of the German chemical industry, and how much national independence would not only rely on politics and economics but also on technology, of which chemistry was an essential part. For these reasons, the future the IACS was questioned as early as 1917.

|

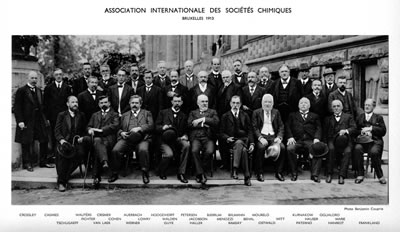

| Group picture of the IACS meeting, 19–23 September 1913, also considered to be the first Conseil de Chimie Solvay. This is the first group picture of the IACS on record. |

Though IACS can be considered the forerunner of IUPAC, there are a few differences that should be stressed. The most striking is the fact that the International Association focused exclusively on PURE chemistry, whereas IUPAC, as its initials suggest, is also focused on applied chemistry. Clearly, IACS’s aim was to organize and standardize chemistry so as to facilitate communication and the exchange of information and results. By encouraging networking at an international level, scientists, and especially chemists, were convinced they were serving the progress of science and humanity. But this noble aim wasn’t exempt from competition or even rivalry.

| And science that had been celebrated as an international venture whose benefits could be evenly shared by all nations suddenly became a national or patriotic pursuit. |

The rhetoric of internationalism at the turn of the century should not be interpreted as a spirit of total cooperation. Instead, what occurred was “Olympic internationalism,” as Paul Forman has labeled this behavior, in which nations attempt to promote international fraternization and national pride at the same time. Thus, it is no wonder that during periods of acute conflict, such as the First World War, national rivalries that had been kept within the boundaries of gentlemanly competition, could turn into strong nationalism. This attitude, though not common, culminated in the Aufruf an die Kulturwelt, also known as the Manifesto of the Ninety-Three, because it was signed by 93 intellectuals and eminent scientists, including Fritz Haber, Adolf von Baeyer, Max Planck, Paul Erhlich, Wilhelm Röntgen, Hermann Emil Fischer, Wilhelm Ostwald, Walther Nernst, Richard Willstätter, Wilhelm Wien, and Felix Klein. In this short proclamation, they declared their total support of German military action at the beginning of World War I and denied any “war crimes” that were blamed on the German army such as the killing of civilians or needless destruction like the burning of the library at the University of Louvain.

|

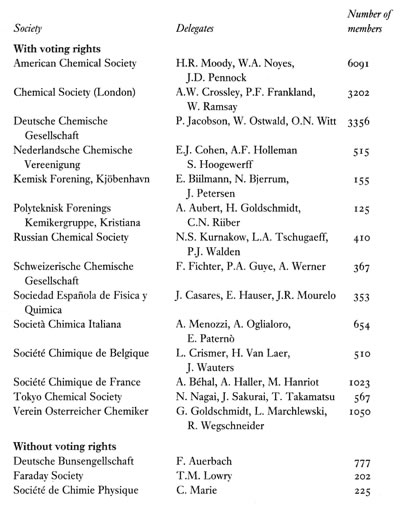

| Membership and Delegates of the the affiliated societies to the IACS in 1913 (from R. Fennell, History of IUPAC, 1919-1987, p. 10) |

Foreign intellectuals and scientists were outraged and this feeling persisted for many years after the war ended. At the same time, the Bureau of the IACS, after having conferred with its member societies decided that it would be impossible to resume fruitful collaboration with representatives of chemical societies of the allies and chemical societies of the central powers. IACS gave the money back to Solvay and disbanded the short-lived dream of international chemical collaboration and standardization. On 28 July 1919, a new international organization, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, was formed, which, in its statutes approved that day, excluded the former enemy countries, including Germany, which had been the leader in chemistry at that time. It wasn’t clear how easily neutral countries would be accepted into this new confederation, but by 1925, politics had moved on, and following the Locarno treatises, scientific collaboration was able to resume. At last, the universal character that had been at the core of the IACS had returned.

Dr. Brigitte Van Tiggelen <[email protected]> is research associate at Université catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-neuve, Belgium and leads Mémosciences, a non-profit organization devoted to the history of sciences. Dr. Danielle Fauque <[email protected]> is reasearch associate at Université de Paris-Sud 11 (Orsay, France) and chairs the Club d’histoire de la chimie, which is the historical division of the Société Chimique de France.

Notes, References, and Further Reading

- 2011 also marks the centenary of the first Solvay Conference in Physics, which gathered eminent scientists such as Albert Einstein, Henri Poincaré, Marie Curie, Pierre Langevin, Walther Nernst, Jean Perrin, Arnold Sommerfeld, Max Planck among other well-known names to discuss the new theories of radiation and quantas. This “Witches’ Sabbath” as Einstein called it became a milestone in the history of modern physics as it raised awareness for the quantum physics.

- Danielle Fauque, "French Chemists and the International Reorganisation of Chemistry after World War I," in Ambix, vol. 58-2 (July 2011), pp. 116–135.

- Fondation de l’Association internationale des sociétés chimiques (AISC) à Paris, www.societechimiquedefrance.fr/produit-du-jour/de-l-aisc-a-l-iupac.html

- Roger W. Fennell, History of IUPAC 1919–1987, Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1994.

- Geert J. Somsen, "A History of Universalism: Conceptions of the Internationality of Science, 1750–1950," in Minerva, vol. 46 (2008), pp 361–379. www.springerlink.com/content/3r44072845r87p78/ (free access)

- Brigitte Van Tiggelen, Les Premiers Conseil de chimie Solvay (1922-1928). Entre ingérence et collaboration, les nouvelles relations de la physique et de la chimie, in Chimie Nouvelle, vol. 17 – n° 68 (December 1999), pp. 3015–3018.

A follow-up feature will appear in the next issue that will cover The Solvay Councils and the International Institute for Chemistry.

Page

last modified 3 January 2012.

Copyright © 2003-2012 International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry.

Questions regarding the website, please contact [email protected] |